The Divine Theophany and Unity of Opposites

Exploring the concepts of Divine Theophany and 'Unio Oppositorum' via the case of Ibn 'Arabi and his spiritual guide, Lady Nizam.

The Divine Theophany

One fateful night, the great Andalusian mystic Sheikh Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi was silently circumambulating the Kaaba. Lost in reverie, he strode amidst a crowd of pilgrims when a gust of inspiration suddenly rushed over, delivering the following verses to his mind, which he recited aloud:

Would that I knew whether they knew

Which heart they possess,

And if only my inner heart knew

Which mountain pass they travel through.

Do you see them as being safe,

Or do you see them as having perished?

Those who are consumed with passion (hawā) are perplexed

In love (hawā) and become confused.1

He felt a light touch on the shoulder. The Sheikh turned around and saw before him a young woman of sublime beauty — a princess from among the daughters of the Greeks2, unmatched in beauty of the face, softness of the speech, and tenderness of the heart. She asked to recite the verses again, and when he did, reproached him with passion:

“…How can they retain a residue of perplexity and hesitation when the very condition of adoration is that it fill the soul entirely?” she said. “It puts the senses to sleep, ravishes the intelligences, does away with thoughts, and carries him away in the stream of those who vanish. Where is there a room of perplexity? . . . It is unworthy of you to say such things.”

The cause of her displeasure was simple — for a moment, the poet succumbed to a minute weakness, questioning his commitment to the Beloved and letting the faculties of critical thought overtake his mystical instincts, and in doing so, inadvertently breaking the purity of his spiritual state:

“He has given in for a moment to the philosopher’s doubt; he has asked questions that can only be answered by rational proofs similar to those applying to external objects. He has forgotten for a moment that for a mystic the reality of theophanies, the existential status of the ‘supreme Contemplated Ones,’ depends not on fidelity to the laws of Logic, but on fidelity to the service of love. Do not ask them whether they have perished; the question is whether you have perished or whether you are still alive, whether you can still ‘answer for’ them, still permit them to invest your being.”3

Laden with symbolism, the nightly encounter by the Kaaba proved to be one of the most pivotal experiences in Ibn ‘Arabi’s life. Later, he came to learn that his mysterious interlocutor was none other than the daughter of the noble Abi Shajaʿ Zahir, a Meccan Sheikh of Persian background and caretaker of the Maqam Ibrahim4. Her name was Nizam, which meant “Harmony”. They were to meet again.

Little is known about Lady Nizam; her writings, if they had ever existed, have been lost to time. All we can rely on are Ibn 'Arabi’s own accounts. In the preface to Tarjumān Al-Ashwāq, a collection of mystical love poems inspired by Nizam, he mentions that he got to know both the young woman and her family well — although it remains unclear whether the two ever got married.

“She was riveting to gaze upon. She adorned the assemblies, delighting whoever was addressing the gathering, and confounding her peers with her beauty and her intellect … She was named “Ayn al-shams wa-l-bahā”— the source of the sun and the glory—one of the women who are learned and who serve God, who are dervishes and ascetics; the shaykha of the two sanctuaries (Mecca and Medina) and the culture of the greatest sacred land (Mecca). The heights of Tihāma shone because of her, and due to her proximity, the meadows opened their calyxes, raising the heights of knowledge through the mystical and spiritual science she possessed. In her were the touch of an angel and the aspirations of a queen.”

Ibn ‘Arabi saw Nizam as far more than a merely terrestrial muse; she was a theophany of the Absolute5, a medium through which one could contemplate God and undergo spiritual annihilation (fana’a).

“A sweet-lipped girl, dark-lipped, honeyed where she is kissed—

The testimony of the bee is what appears in its white, thick honey”

Throughout Tarjumān, he does not shy away from using sensual language6 to praise the physical beauty of his beloved alongside her spiritual gifts. Startling as it may be for anyone who views any expression of erotic desire as imminent corruption, it, in fact, perfectly aligns with the rest of the Sheikh’s non-dualistic philosophy, as it integrates the religious, romantic, and erotic elements into a unified and uncompromised whole. Flesh and spirit are treated as inseparable from each other, so to spurn or minimize the outward beauty of the woman, to refuse to revel in it, and to view it merely as a worldly illusion and distraction from “real” spirituality, is akin to rejecting a fundamental part not only of the beloved, but, by extension, of reality itself.

The secret of Lady Nizam lay in harmonizing both the physical and spiritual aspects, thereby achieving what one calls the divine beauty; completeness. And it is this completeness and totality of being that led Ibn ‘Arabi to see in her not only a woman endowed with striking physical presence and of considerable spiritual stature, but also an initiatrix into greater and ever more subtle mysteries of the unseen.

The role of Lady Nizam could be compared to that of Beatrice of Dante Alighieri7, and upon closer examination, one can notice parallels between the poetry and philosophy of Ibn ‘Arabi and the Fedeli di Amore (of which Dante was a part), the medieval European brotherhood devoted to the ideals of “courtly love” — a concept of secretive romantic love, typically between a knight and a noblewoman, wherein the female beloved is seen as an embodiment of and a conduit for the Divine. When viewed from this perspective, the image of Lady Nizam becomes synonymous to Sophia aeterna, the female archetype of wisdom and guide towards higher realities.

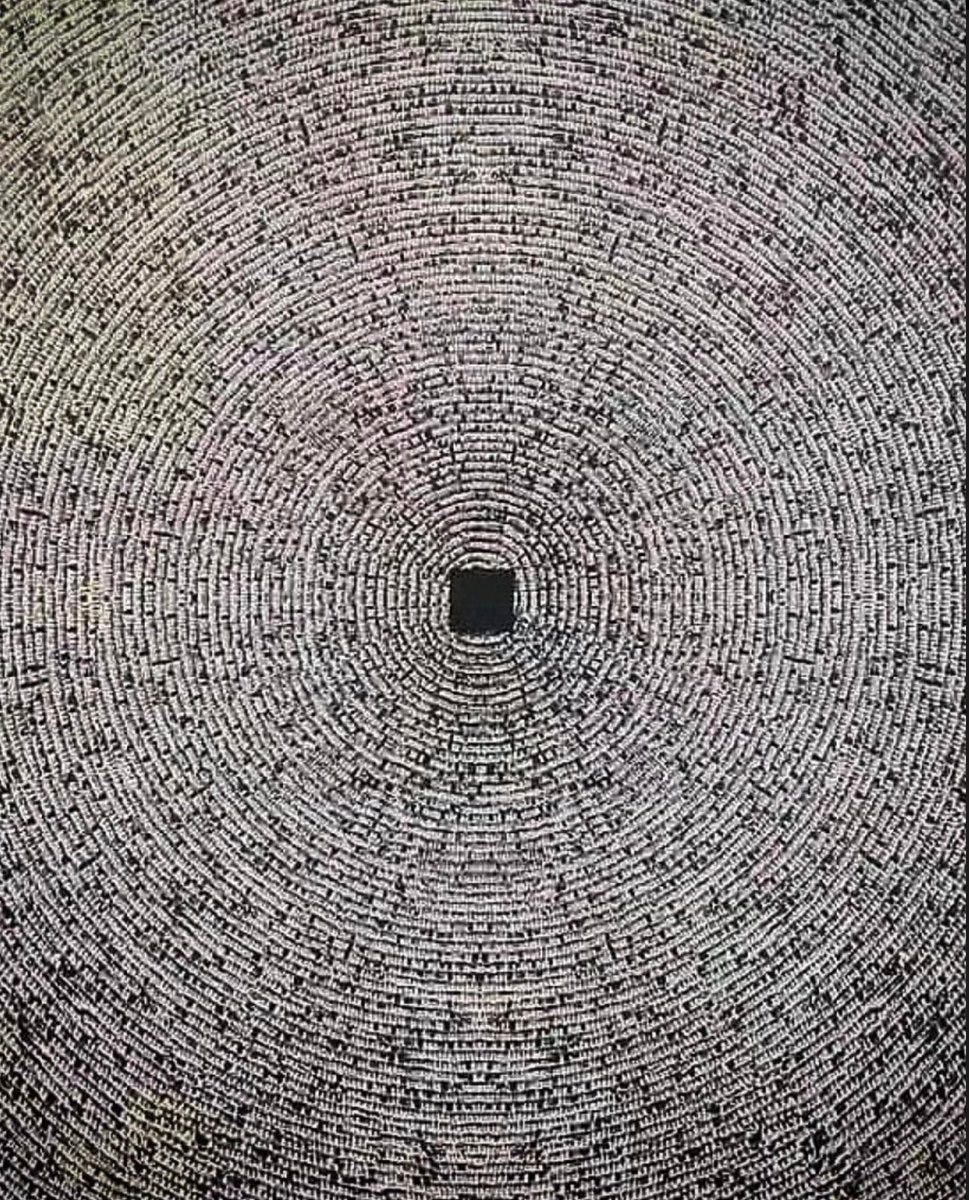

It is highly symbolic that the meeting took place as the Sheikh was circumambulating the Kaaba. In Islamic spatial consciousness, the Kaaba occupies a central position, akin to an Axis Mundi — a mythogeographic point that connects both the earthly and heavenly realms. It serves as a sign of cosmic order, divine oneness, and ultimately, harmony, uniting all four cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west at its enter.

In Fusus al-Hikam, Ibn ‘Arabi goes as far as to state that woman represents the most perfect medium for witnessing God’s theophany (tajallī):

“When man witnesses God in women, his witnessing is in the passive; when he witnesses Him in himself, regarding the appearance of woman from Him, he witnesses Him in the active … So his witnessing of God in the woman is the most complete and perfect because he witnesses God both in active and passive. Regarding himself, He is passive in particular. For this reason, the Prophet, may God bless him and grant him peace, loved women because of the perfection of the witnessing of God in them since one does not ever witness God free of matter. God by His essence in independent of the worlds ... The witnessing of God in women is the greatest and most perfect witnessing. The greatest union is marriage.”

When Adam witnesses his Lord within himself, and meditates on himself and his role in relation to Eve, his witnessing is solely in the active mode. When he witnesses himself without Eve, his witnessing is solely in the passive mode. And so, in the quest to attain the ideal synthesis, he must contemplate the Lord in Eve whose being, in relation to Adam, is both active and passive. Through this, the perfect reciprocal equilibrium of active and passive modes is achieved.8

The Divine Names and Unity of Opposites

This echoes another important concept: that of God's Divine Names, through which a person recognizes God’s activity in the world and begins to see all their surroundings as theophanies. The Names are traditionally categorized into two sections: jalāl (majestic) and jamāl (beautiful), each respectively associated with male and female essences. Names of Majesty stress the importance of governance, law, and traditional values, reinforcing the role of man as God’s vicegerent over nature, and as guardian of social order and moral conduct. Examples of such names include God the Sovereign, the Afflicter, and the Arbiter of Justice.

On the other hand, Names of Beauty highlight the importance of love, grace, and forgiveness. To support this, Sufi mystics cite the Arabic words “rahim” (mercy) and “rahm” (womb) to draw the connection between God’s Mercy and motherhood. God’s Mercy is likened to a Womb that sustains all elements of creation at every moment of existence, and God is often invoked and meditated on as the Greatest Forgiver, the Embodiment of Peace, and the Most Loving.

“Know before everything else that Mercy is primarily exercised in bringing everything into existence, so that even the torments of Hell themselves have been brought into existence by Mercy that has been directed toward them.”9

Both jamāl and jalāl, although appearing as polar opposites on the surface, reflect two distinct aspects of Reality and complement each other like Adam and Eve, Pen and Tablet, Sun and Moon. Neither one is solely receptive or active, and each contains within itself a glimmer of the opposite. The Tablet provides the foundational canvas on which the Pen can write, delimit and concreticise the virtual possibilities inherent in the Tablet.

You are the form of the image of the Named,

That is why you know all Names.10

Elsewhere, Ibn ‘Arabi states that the Absolute is best known through a synthesis of opposites. Abu Sa'id al-Kharraz, a prominent 9th-century Baghdadi mystic, too, postulated that “God cannot be known except by attributing opposites to Him simultaneously.” It follows from this that the universe is a stage for the amorous interplay between Divine Names of opposite qualities, always and continuously in motion, but ontologically downstream from One Essence. And this is why the goal for every person on the non-dual path, whether man or woman, is to achieve harmony by reconciling these opposites within — and remembering that Reality is One in all, and encompasses all that exists.

I will conclude this essay with a poem from “Tarjumān Al-Ashwāq” to honour the beautiful Lady Nizam, the embodiment of Divine Love:

When she kills with her glances, her speech restores to life,

As tho’ she, in giving life thereby, were Jesus.

The smooth surface of her legs is like the Torah in brightness,

And I follow it and tread in its footsteps as tho’ I were Moses.

She is a bishopess, one of the daughters of Rome, unadorned:

Thou seest in her a radiant Goodness.

Wild is she, none can make her his friend;

She has gotten in her solitary chamber a mausoleum for remembrance.

She has baffled everyone who is learned in our religion,

Every student of the Psalms of David, every Jewish doctor,

And every Christian priest.11

From “Preface to Tarjumān Al-Ashwāq”

Ibid.

From “Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi” by Henry Corbin, p.143

“Maqam Ibrahim”, or the “Station of Ibrahim”, is a small stone used by the Prophet Ibrahim (as) throughout the development of the Kaaba.

For further clarification on the Absolute Being and the gradations of God’s self-disclosure, see “God as The Hidden Treasure and the Absolute Being.”

On the use of erotic imagery in poetry, Ibn ‘Arabi states, “I allude in these [pages of commentary and poetry] to lordly gnostic learning, divine lights, spiritual secrets, noetic sciences, and admonitions based on the Islamic tradition; I rendered the expression of all this in the language of the amorous lyric [ghazal] and playfully erotic poetic depictions [al- tashbib], because souls fall passionately in love with such expressions.”

Miguel Asín Palacios in “La Escatología musulmana en la Divina Comedia” argued that Dante, directly or indirectly, drew inspiration for “Divine Comedy” from medieval Muslim thought, and the philosophy of Ibn ‘Arabi in particular; for more, see “Esoterism of Dante” by René Guénon.

For further elaboration on this subject, I suggest referring to Muʾayyid al-Din Jandi’s and Abd al-Razzaq al-Kashani’s commentaries of “Fusus al-Hikam”.

From “Sufism and Taoism” by Toshihiko Izutsu, chapter “Ontological Mercy”.

From “The Mystic Rose Garden (Gulshan-i Raz)” by Mahmoud Shabistari.

Poem 2 in “Tarjumān Al-Ashwāq”, translated by R. A. Nicholson; also check the song version performed by Ensemble Ibn ‘Arabi.

This is a very beautiful writing… 🩷

It means mercy here too, but knowing that it also means 'womb' and how the scholars brought those two concepts together was like when the etymology of a word dawns on you. Deepened the word's meaning.