Returning Home

Thoughts on the Hero's Quest and the Return Home

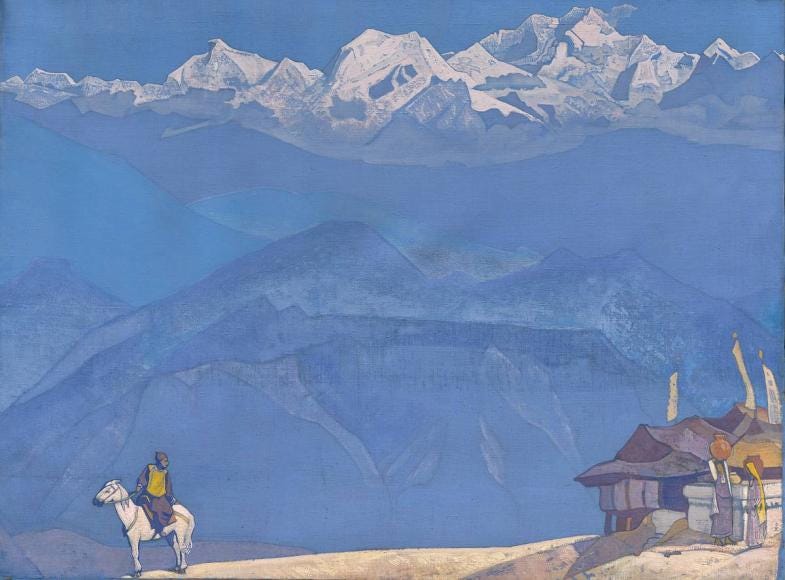

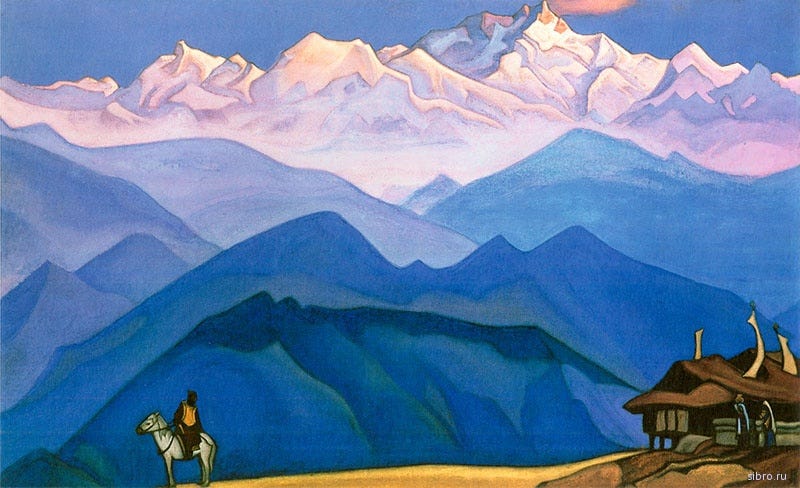

There is a famous painting by Nicholas Roerich titled “Remember”, of which two slightly different versions exist. In both, a lone rider on a horse casts a farewell glance at his familial home and the two women who are seeing him off. Behind, in the background, rise the majestic, snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas.

The rider is about to embark on a journey; he knows that regardless of where fate takes him, he must not forget his past, home, or the greater purpose; he must remember why he is leaving, and why he must return home again.

The theme of painting was inspired by the artist’s own life path: Roerich left his home country of Russia in 1918 following the Revolution, first moving to Europe, then the United States, and finally settling in India. Russia, however, remained integral to his artistic and philosophical explorations. Like many of his contemporaries, Roerich saw it as bestowed with a unique spiritual mission, and has repeatedly tried to arrange a return home. Towards the end of his life, he created a second version of “Remember” (1945)—the painting is done in noticeably more somber and melancholic tones than the first, likely reflecting artist’s internal state at the time. Roerich died in exile in India in 1947, having never set foot in Russia again.

“Remember” taps into a perennial narrative found in countless epics, legends, and tales: a hero’s journey. A man sets off on a quest—physical, spiritual, or both—and faces a series of challenges and trials, which often put him on the brink of death. Finally, he defeats his enemies and returns home, transformed by everything he has experienced and witnessed along the way.

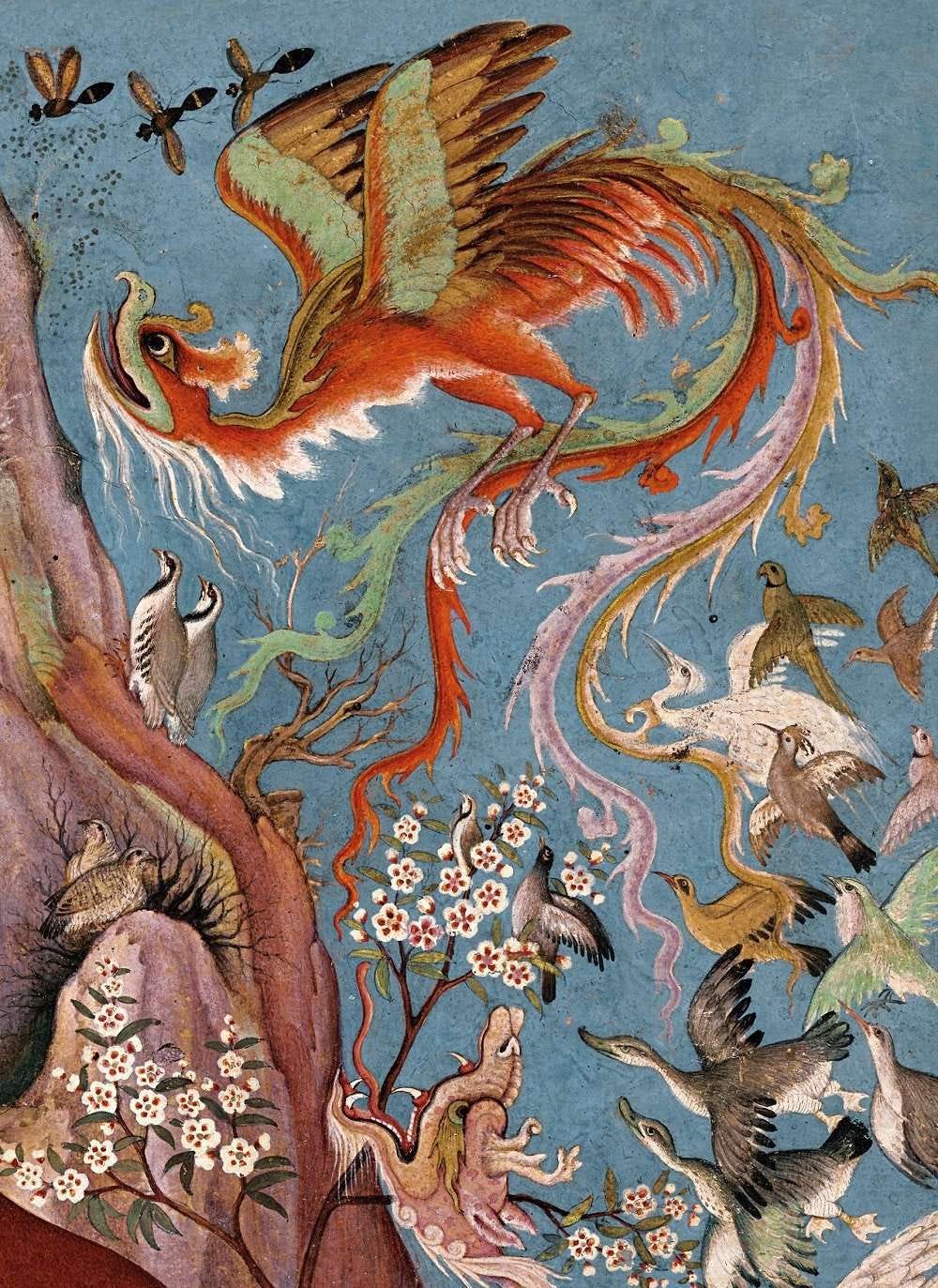

Sometimes, however, there is no physical return trip home; rather, the hero comes to realise that the home he has been looking for and yearning to come back to is within, as was the case in Fariduddin al-Attar’s poem “The Conference of the Birds”. The birds, having set out on a journey, persevere through various obstacles and tribulations as they travel across the seven valleys (representing seven stages of enlightenment) to meet the King of the Birds, the great Simurgh, at Mount Qaf1; some of them make it to the end, but the majority do not. When, at last, they arrive at the King’s abode, they discover that Simurgh is a reflection of the remaining thirty birds, and that the ultimate Truth lies within themselves:

How much you thought you knew and saw; but you

Now know that all you trusted was untrue.

Though you traversed the Valley’s depths and fought

With all the dangers that the journey brought,

The journey was in Me, the deeds were Mine –

You slept secure in Being’s inmost shrine.

And since you came as thirty birds, you see

The Simorgh, Truth’s last flawless jewel, the light

In which you will be lost to mortal sight

Dispersed to nothingness until once more

You find me in the selves you were before.’

Then, as they listened to the Simorgh’s words,

A trembling dissolution filled the birds –

The substance of their being was undone,

And they were lost like shade before the sun;

Neither the pilgrims nor their guide remained.

The Simorgh ceased to speak, and silence reigned.2

Often, when we long to return to our old home or past, what we really long for is to return to a particular state of consciousness, of which a corporeal place is just a symbol. So, in the esoteric sense, returning home means returning to one’s true self, to the original, paradisiacal state of wholeness and unity that we remember most vividly in childhood; nor does the internal home necessarily correspond the the physical place. But the path is long and demands many sacrifices, such as leaving behind one’s material home, family, wealth, old beliefs, and even risking one’s life—all to attain the ultimate Truth.

At different points in my life, I felt like the rider in the Roerich’s painting. After all, I too, have left my childhood home and town behind to pursue a higher goal, and there are many others like me who sacrificed the soothing comfort of their surroundings to follow a calling. This August, I came to my hometown for a family visit and once again, I felt the urge to stay, to slip back into old habits and patterns, to lead a quiet and unassuming life in a place that expects nothing of me; to retreat into the familiar, both consoling and soothing, like deep sleep or a mother’s womb. The world outside appeared a polluted, corrupted place, replete with unending cruelties and demands that one must either accept or be crushed. Why would you pursue any goal, when nothing may come out of it? Worse yet, what if everything you ever thought of yourself and your purpose may well be a complete delusion? Perhaps you never had what it takes to make it, or perhaps the circumstances are not in your favour; perhaps they never have been. Why fight an uphill battle? Isn’t it better to simply withdraw into the shadows where you don’t have to prove anything to anyone—least of all, yourself? Stay, stay, just for a little longer!

There is a certain allure to the idea of leaving everything and moving away to outskirts, or a part of the world we deem pristine and free of social maladies and fast pace of modern life. With friends, we often like to joke that had we been born in a different era, we would have become ascetics, wandering mystics, nuns, and monks. The figure of the hermit or anchorite, who renounces the material world and its luxuries to follow a spiritual path, has always resonated with me, and it is becoming increasingly more appealing to many in modern world. However, I also understand that much of it is driven by a fantasy—what fuels the impulse to leave is largely a feeling of being overwhelmed by one’s environment rather than unconditional devotion to the Divine. One would not withdraw out of a genuine calling (which, in such a case, would be the undertaking of an internal journey), but out of weakness and inability to overcome oneself.

Had I given in and settled, things might have been fine for a while; but soon enough, I would come to loathe everything and everyone, and most of all, myself. The obsessive desire to return to the past, to the home as one once knew it, or even to a different age or reality that no longer exists, is a path of an escapist and is futile, for it leads one away from their internal home and into nowhere. To decline the invitation to journey or to return prematurely is to succumb to external forces and thus lose agency over one’s fate.

Retreating is and always will be an option, but choosing to face reality as it is—by seeing through its chaos and uncertainty, and not turning back but asserting one’s will within it—is how one transcends the grip of the exterior world. And ultimately, this is what sets the great apart from the rest—the ability to stay on their chosen path, unshaken, even if it costs them everything in the process.

“Against the backdrop of the mighty heights of the Himalayas, at a time when everything below is still shrouded in purple mist, while the mountain peaks are already illuminated by the gentle, renewing rays of dawn, a rider stands at the edge of the slope, parting with the highlands to undertake the journey of his life. He glances back one last time with sadness, perhaps hearing the words of his mother, standing by the mountain hut: ‘Go, fight, create, but do not forget the mountains and homeland. Carry them in your memory throughout your life, and keep them in your heart as you strive toward your cherished goal.’”3

Mount Qaf is a sacred mountain in Persian and Arabic mythology. It is often described as the dwelling place of legendary birds such as Simurgh or Anqa. In almost all traditions, including the Islamic one, a mountain represents spiritual ascent, with the peak symbolizing the highest level of spiritual enlightenment.

From “The Conference of the Birds”, translated by Dick Davis.

From “Cosmic Strings in the Works of Nicholas Roerich” by Richard Rudzitis.

Perhaps we love visiting the places we have left behind because we can get away from them whenever we choose to. I distinctly remember that I thought of my hometown as a large, suffocating prison as a child, because there wasn't much to do and one couldn't look very far off into the horizon because of the large hill in the front. It was like waking up and staring at a towering green wall everyday, obscuring the world from me. Time tamed that view, but I think it still is a valid sentiment. One can have a taste of the past every now and then, but succumbing to it can be fatal. Wonderful meditation, Yana.

Very sober remarks - not retreating to the comforts of delusions. Most people are on this treacherous path especially due to modernity (i.e. full of delusions about entitlements, conveniences and promises of luxury), that the state of pristine wanderers (e.g. in Mauritanias deserts) may actually be one of the few authentic paths back. For they prioritised the neglect of the ‘demands’ and (self) expectations of our times. Perhaps this is not for everyone choosing to journey back. After all, the return is essentially a symbolic/internal one rather than an outward attempt. It is about the direct encounters with and taste acquired from these experiences. But, alas, most can’t make it - as you point out with The Conference of the Birds. Those who can return see with their inward eye. They love the true journey of return and always prepare for it.